Ah, the Hero's Journey. The monomyth. Calls to action, friends made and lost, challenges overcome, good triumphing over evil. Lovely stuff. And for some time now it’s been a useful tool for content marketers to deploy in order to guide their customers through the buyer's journey. Positioning the buyer as the hero in their own story and helping them triumph over their problems by buying your product has become a staple part of many marketers’ toolkits. But does it still hold up?

What the heck is a monomyth?

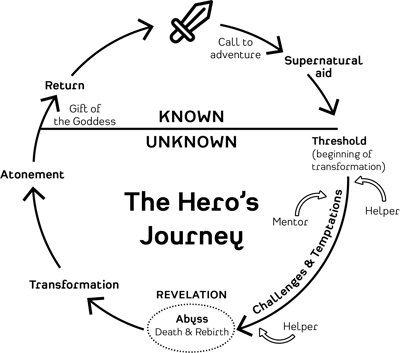

As with all good journeys, we should start at the beginning. The Hero's Journey (also known as the monomyth) is a frequently used (arguably overused) narrative archetype. In stories based on the Hero's Journey a hero receives a call to action that they cannot ignore. They go on an adventure, learn a lesson, use their newly acquired knowledge to win a great victory, and then return home transformed by the experience.

First described by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, the monomyth has been used as the basis of literally thousands of movies, tv programmes, books and games, sometimes in a more compact form to deliver the main thrust of the narrative in a shorter time frame. The standard examples everyone trots out when writing these articles are Star Wars, Harry Potter, The Matrix, The Lion King, just about any superhero origin story… It can also be applied to Quantum Leap, The A-Team and possibly other tv programmes that aren't from the 80s, I haven't checked. But the list just goes on and on. There are many, many, many articles breaking down just how the Hero's Journey was applied in these examples (possibly not for Quantum Leap) so I won’t go into too much more detail here and will assume you get the gist.

How the Hero's Journey is applied to content marketing

In content marketing the Hero's Journey is used to help customers find a better way to overcome an issue in their lives and achieve their goals. It helps companies and organisations think closely about the products or services they are delivering to the customer and how those products solve a problem. Then guides the customer along the journey from awareness to purchase. Once the customer has bought into the product/service they can become a hero in their own right by sharing that solution and helping others overcome similar problems.

Isn’t this just AIDA?

A typical customer journey outlines the path a customer will travel from beginning to end to solve a problem. Often beginning with the awareness stage (the call to action in the Hero's Journey) and finishing with a purchase (the transformation and return). The fundamental elements of this journey follow the AIDA model (Attention, Interest, Desire, Action), and many marketers are content with this bare bones approach, or unaware of the steps they need to take to actually deliver a Hero's Journey to their customers. But where the Hero's Journey differs from AIDA is that AIDA alone doesn’t really reflect what happens in a well constructed multi-channel marketing strategy. Using the lifecycle stages that AIDA encourages will help to answer some of the questions customers have at any given time, but it isn’t bringing them along on a journey, acting as a mentor that guides them through the process from start to finish. Essentially, your content is not being set up as a story in which the customer is the hero, leveraging the very human need for storytelling, and delivering psychological triggers that encourage customers to proceed further along the journey.

With a properly executed Hero's Journey you would instead look to build all of your current and future content as though it were part of a novel, delivering chapter after chapter (or article after article, whitepaper after whitepaper, video after video) that frames the customer as the hero and delivers the right message to the right person at the right time, at scale.

So, tactically, your content marketing strategy would view each ad, landing page, email, demo, sales call, etc as a chapter in that story. Each element delivers the next thrilling instalment that compels your customers to continue their quest, with you acting as their mentor and guiding them safely through the perils ahead. Calls-to-action become the cliffhangers that encourage those next steps. And at every step of the journey the customer actively chooses to continue of their own volition, not following pressure from your marketing and sales teams to do so.

Right. Got it. I’m onboard with the Hero's Journey. So what’s the problem?

Well, there have been a number of criticisms levelled against Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. I don’t intend to cover these in great detail in this article but I do want to touch on a few key criticisms that apply to the intended use of the monomyth (story telling in its traditional sense) and the application of the Hero's Journey to content marketing.

Firstly, and relevant for any of you dealing with customers outside of the western world, critics of Campbell’s monomyth have suggested that it is too western in its approach and lacking in global understanding. There are similar myths and stories told in many countries across the world, but the message delivered in those stories and the approaches to problem solving can differ widely from culture to culture.

Second, there isn’t always a clearly defined beginning, middle or end to our stories. Nor is there always a clearly defined path that our customers will follow on their journey. On a personal level, stories that occur in our lives are often short, spanning mere minutes or hours where there simply isn’t the time or the need to deliver a full blown narrative in order to convince us to make a purchase.

Third, once your hero completes their journey, what comes next? What happens to all the energy and excitement nurtured by your carefully constructed narrative? Without careful attention it dissipates, and retention and development then become something of a disappointing sequel, like everything after the original Jurassic Park, or how I imagine the reboot of Quantum Leap is going to pan out. Whatever comes next needs just as much care and attention devoted to it in order to keep that customer loyal, and develop them as advocates of your brand.

Fourth, following the Hero's Journey runs the risk of simply following a checklist exercise. In a sense, it discourages originality. The same stories are told time and again without room for creativity or (for organisations) finding new ways to guide your customers from awareness to purchase.

Finally, the Hero's Journey itself is beginning to lose relevance in the 21st century. Not because it fails to tell a good story (even if it is a bit overdone at this point. Quantum Leap ended in 1993 after all) but because society itself is changing, and with it our desire for more complex narratives is emerging. Media has changed at a frankly alarming pace with the emergence and prevalence of social media. As people have ever increasing opportunities to connect and collaborate, our stories are beginning to shift focus from individual growth to societal and cultural connection. If that is the case, then the Hero's Journey becomes limited in its ability to deliver stories that resonate across interconnected cultures and societies.

Enter the Collective Journey

So if the Hero's Journey doesn’t pass muster anymore, what should organisations be doing to guide their customers? Geof Gomez, CEO of Starlight Runner Entertainment proposes that we have moved beyond the Hero's Journey and into the collective journey. Where previously stories had followed Luke Skywalker, Harry Potter, Simba or Neo across the journey from start to finish, now we follow stories where the ‘central’ character doesn’t always save the day, doesn’t always follow a strict moral code, and doesn’t always see the story through to its end. Think Ned Stark in Game of Thrones (or A Song of Ice and Fire if you prefer the books), brutally executed in the first series (book), Rick Grimes in The Walking Dead, who disappears before the conclusion of the story, or Piper in Orange is the New Black, described by the show’s creator, Jenji Kohan, as a trojan horse:

“In a lot of ways Piper was my Trojan Horse. You’re not going to go into a network and sell a show on really fascinating tales of black women, and Latina women, and old women and criminals. But if you take this white girl, this sort of fish out of water, and you follow her in, you can then expand your world and tell all of those other stories.”

These ensemble shows familiarise us with large casts of characters with different motivations, problems, adversaries and challenges to overcome. Often in direct competition with others in the story. A little more like day to day life for us regular 21st century Earth folk.

By adopting collective journey stories over the Hero's Journey approach we shift the narrative from focusing on an individual’s quest to overcome an adversary, to looking at systems in need of repair. Collective Journeys, Gomez argues, are about “how communities actualise in their attempt to achieve systemic change”. We begin to explore new ways of telling, participating in, and analysing narratives, encouraged and enabled by new technologies that allow us to respond and interact with stories as they emerge, at a pace unfathomable just a few short years ago.

The Collective Journey approach doesn’t suggest that stories are without conflict, but that the nature of conflict is changing and the stories we tell our audience (or customers) need to change to fit this new world, and tell people what they need to know. The key to all of this is listening.

To switch back to talking about organisations directly, when we analyse customer data to plan the perfect journey for our customers, we are searching for answers and understanding without directly listening to the customers themselves. If we look purely at raw data we run the great risk of imposing our own narrative onto a completely different story. Instead we need to adapt, listen to our audience and accept that the story is more fluid, and nuanced than we have seen before.

So how do we start going about building a Collective Journey? We’ll cover that in the next article.

Featured Photo by Andres Iga on Unsplash